Originally published on Open Democracy.

The cotton fields of Uzbekistan are tied to the tree-lined streets of upmarket Geneva by the empty vaults of a Russian bank and a British limited liability partnership.

The country, which the Tax Justice Network calls “the grandfather of the world’s tax havens”, is a magnet for those with riches of ambiguous origin. Many choose to maintain opulent Swiss residences close to their offshore assets. One example can be found on a private road in Vandoeuvres where Russian-Armenian businessman Agadzhan Avanesov lives. A society piece in the Swiss press describes him as a “discreet man who does not like to expose himself publicly”, with an interest in collecting art, cars and watches.

The Russian authorities offer a less complimentary description. They claim Agadzhan Avanesov is one of the men behind an alleged scheme that saw Russia’s Starbank go bankrupt in 2016 with US$200 million in liabilities.

In correspondence with the author, Avanesov stated: “After revocation of [its] banking licence, Starbank was subject to investigation [by] the competent authorities of the Russian Federation. Not being a participant of this investigation, I do not know its state and I cannot comment [on] it.”

A new report by Ulster University and the Uzbek Forum for Human Rights traces a money trail in Russian court judgements that leads from Starbank to a flagship initiative to privatise Uzbekistan’s cotton and textile industry.

Without rigorous corporate due diligence checks, the Uzbek government’s cotton privatisation initiative has opened the door to potential abuse. The use of British companies highlights the UK’s role in this opaque process, and publicly available corporate data and court records raise questions about how closely the Uzbek authorities are monitoring privatisation.

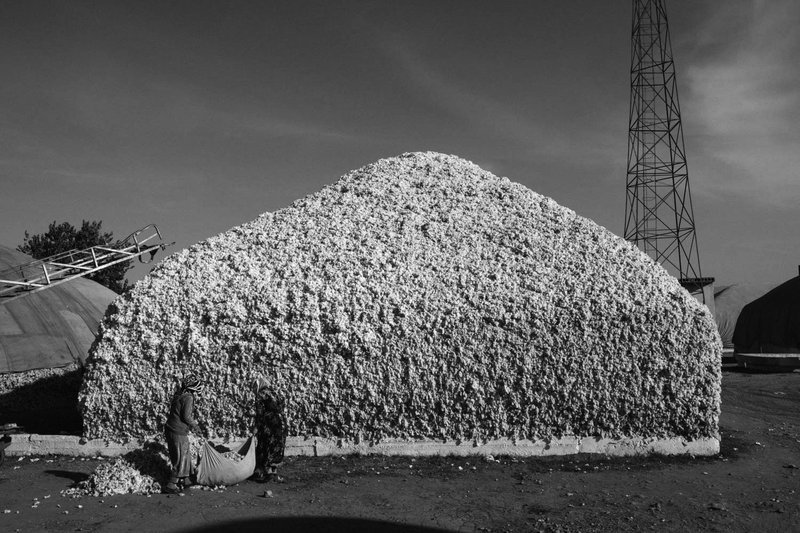

Uzbekistan’s cotton revolution

Up until recently, students, medical workers, teachers and public servants, to name just a few of the targeted groups, were press-ganged into the cotton fields of ostensibly privately owned farms by the Uzbek government. Farmers themselves faced gruelling targets and received derisory farm-gate prices. The forced labour programme eventually prompted international brands to publicly commit to avoid using Uzbek cotton in their supply chains.

Now the private sector is being invited in to turn things around. In a bid to revitalise the sector, and end the international pledge on avoiding Uzbek cotton, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s administration has rapidly privatised cotton production.

Court records relating to Starbank’s implosion indicate the selection process for the cotton privatisation initiative has adopted a “pragmatic” approach to investment, as advocated by Uzbekistan’s First Deputy Minister of Economic Development and Poverty Reduction. “You have to be pragmatic… the most important thing is whether an investor makes an investment or not,” the deputy minister said – regarding a US$1.3 billion construction project that has exhibited serious due diligence red flags and conflicts of interest.

According to Russia’s Central Bank, Moscow-based credit institution Starbank failed “to comply with federal banking laws” and “was involved in dubious operations to withdraw funds overseas”. This prompted the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs to launch a criminal investigation into theft of bank property in 2016. The Russian authorities believe that bank insiders stole depositors’ funds. Bad loans, they argued, were a key conduit for the fraud.

Agadzhan Avanesov was chairman of the board at Starbank and, according to Russian Central Bank records, he was also a 19.7% shareholder via a Swiss company. Through British offshore vehicles, Avanesov and a closely tied Kyrgyz businessman own Uzbek companies that guaranteed bad Starbank debts worth over $20 million. These companies are at the centre of the privatisation programme for Uzbekistan’s cotton industry.

Avanesov contests the accuracy of the Russian Central Bank records, stating: “I have never been the largest single shareholder of Starbank. I have only been a representative of one of the minor shareholders of Starbank.”

When asked about the companies’ investment in Uzbekistan, Avanesov said: “Most probably your source of information is inaccurate,” and that the cotton privatisation project in question “was never realised”.

The study found no record or government decree confirming that the cluster award to Beshariq Tekstil has been withdrawn.

Ownership chain

Russia’s Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA) currently acts as the trustee for the failed Starbank. It has been tasked with raking back some of the bank’s bad debt. In a 2019 report, the DIA stated that Avanesov and his senior colleagues at Starbank knowingly provided loans, without adequate collateral, to legal entities unable to service the debt. The Russian authorities also claim bad loans were one of the key fraudulent conduits used to steal depositors’ funds.

An investigative report published by Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta in 2018 claims that several Russian companies (unrelated to the present study) owned by Avanesov benefited from these bad loans. In an email to the author, Avanesov denied any impropriety alleged against him by Novaya Gazeta.

Russia’s DIA has initiated legal action against a wide range of companies in a bid to seize Starbank collateral. Two Uzbek companies, Amudaryotex LLC and Beshariq Tekstil JSC, have been taken to court in Russia over US$21 million in defaulted loans provided by Starbank.

In 2018-2019, Uzbekistan’s Cabinet of Ministers awarded cotton clusters – commercial contracts for organising value-added cotton production in specific regions – to these Uzbek companies: Amudaryotex LLC received a 7,000-hectare cotton cluster in Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan region and, on the opposite side of the country, Beshariq Tekstil was selected to operate an 8,000-hectare cluster in Fergana’s Beshariq district.

But the people controlling these companies were far away from Uzbekistan.

At the time the cotton clusters were awarded, an English limited liability partnership called Vertical Alliance LLP held a 94.17% stake in Beshariq Tekstil, while Amudaryotex LLC was a fully owned subsidiary of British company Welroy Technology Ltd. For a period, Vertical Alliance LLP and Welroy Technology Ltd shared a registered mailbox address: 8 Shepherd Market in Mayfair, London.

That doesn’t mean that the people in charge were British. We know who they were because under transparency reforms, limited liability partnerships must disclose their beneficial owners. Vertical Alliance LLP initially declared one primary beneficiary, Ripsime Ambartsumyan, Agadzhan Avanesov’s wife. In 2019, Agadzhan Avanesov and his assistant Vakhid Artykov became the company’s primary beneficiaries in her place.

In 2016, Welroy Technology declared one beneficial owner, Mirakbar Yakubzhanov, a businessman from Kyrgyzstan. Yakubzhanov is tied to Avanesov through shared interests in Uzbekistan.

While Vertical Alliance holds the majority stake in Beshariq Tekstil, an Uzbek company called Genmark Furniture holds a minority interest. Genmark Furniture’s largest shareholder is Mirakbar Yakubzhanov, owner of Welroy Technology, which in turn owned Amudaryotex LLC. Until 2010, Vertical Alliance was known as Genmark LLP.

Recovering the debts

At current exchange rates, in 2013 Starbank made approximately US$21 million in loans to two Russian firms – Beshariq Tekstil LLC and Amudaryatex LLC. The previously mentioned Uzbek companies, Beshariq Tekstil JSC and Amudaryotex LLC, acted as guarantors.

In March 2016, the Russian firm Amudaryatex LLC withdrew €5.8 million (approx. US$6.58 million) of its loan. By this time, Beshariq Tekstil LLC had three Starbank loans, totalling US$15.5 million.

Both Beshariq Tekstil LLC and Amudaryatex LLC, the two Russian firms, defaulted on their loans in March 2016. Later that month, Starbank’s banking licence was revoked. By October that year, the bank had been declared bankrupt.

During 2018 and 2019, the Moscow City Arbitration Court found the two Uzbek firms, Beshariq Tekstil JSC and Amudaryotex LLC, liable for the Starbank loans. A public auction of collateral has been ordered.

Russia’s Deposit Insurance Agency has also taken steps to hold senior Starbank operatives personally liable, including seizing the Moscow apartment of Agadzhan Avanesov. Meanwhile, in 2019 Russian media reported that Avanesov was wanted by Russian authorities on criminal charges relating to Starbank’s implosion.

Avanesov commented: “If I was really wanted by the Russian authorities, I had to be arrested when I crossed a state border. An absence of such actions by Russian authorities confirms that said announcement was baseless and fictitious.”

When asked about the use of Starbank loans for the two cotton cluster projects, Avanesov responded: “Vertical Alliance LLP never invested in Uzbekistan’s new cotton cluster system. Most probably your source of information is inaccurate.”

The authors of the Ulster University and the Uzbek Forum for Human Rights study provided Avanesov with a copy of the Uzbek Cabinet of Ministers decree that awarded Beshariq Tekstil an 8,000-hectare cluster. He commented: “Indeed, local authorities (Fergana region’s administration) included Beshariqtekstil (being a textile factory of Beshariq district of Fergana region) in the governmental resolution referred by you. But this cotton cluster has not been realized.”

As mentioned above, no record or government decree could be located confirming that the cluster award to Beshariq Tekstil has been rescinded.

Avanesov denies any impropriety alleged against him by the Russian Deposit Insurance Agency and Novaya Gazeta. “I have never been the largest single shareholder of Starbank. I have only been a representative of one of the minor shareholders of Starbank,” he wrote via email.

As noted above, this conflicts with filings available from the Central Bank of Russia which identify Avanesov as the equal largest shareholder in Starbank through his Swiss holding company Cage Holding SA, which is currently in liquidation.

Avanesov did, however, lodge an appeal against the court decision to seize his Moscow apartment. Recent court reporting indicates this appeal failed. Avanesov states this is only a “provisional measure under [the] bankruptcy case”.

Records in Russia, Uzbekistan and the UK indicate that Starbank made significant loans to Russian companies Beshariq Tekstil LLC and Amudaryatex LLC. As described above, guarantees for the loans were provided by Uzbek affiliates of the same or similar name which were controlled by Avanesov and his associates. Following successful litigation, Russia’s DIA is now caught in the challenging position of cross-border asset recovery.

It is unclear what happened to the $21 million in loans defaulted on by Beshariq Tekstil and Amudaryatex.

All this information was on the public record at the time Avanesov’s Uzbek interest, Beshariq Tekstil JSC, was appointed to take part in the Mirziyoyev government’s cotton cluster initiative. This points to flawed due diligence, and the consequential high levels of corporate risk this has generated in the cotton cluster system. It also prompts questions on the origins of funds being invested in Uzbekistan’s cotton clusters.

Things fall apart

In 2019, shares in the Uzbek company Amudaryotex LLC were transferred from UK company Welroy Technology Ltd to Textile Technologies Group, which Uzbek media refer to as a South Korean company. Textile Technologies Group has been awarded four other cotton clusters. With the group’s acquisition of Amudaryotex LLC, its cluster holdings cover 46,404 hectares, spread over five districts. This makes Textile Technologies Group an important player in Uzbekistan’s cluster system.

Documentary evidence indicates that Textile Technologies Group and Welroy Technology are in fact owned by the same family. Remember that the beneficial owner of Welroy Technology, from 2016 at least, was Kyrgyz businessman Mirakbar Yakubzhanov. In 2019, a CV used by Murat Yakubzhanov, the son of Mirakbar Yakubzhanov, said that he has been the owner of Textile Technologies Group since 2011, as well as Metal Engineering Group, which owns shares in Genmark Furniture. Currently, Murat Yakubzhanov is a director at state-owned Uzpromstroybank, and a partner at Grant Thornton Uzbekistan. He did not reply to email and written correspondence seeking comment.

In correspondence with the author, Avanesov notes that his business relationship with his former business partner Mirakbar Yakubzhanov has soured. He says that Murat Yakubzhanov gave evidence in the Swiss Federal Court case against Mirakbar Yakubzhanov last year that ended with Avanesov being awarded US$1.33 million in damages in this case. Yakubzhanov senior was also, allegedly, found criminally liable for defamation and libel.

It has not been possible to independently verify Avanesov’s account of this legal process. The author has seen a heavily redacted copy of a decision by the Swiss Federal Court on 14 November 2019, which indicates that a citizen of Kyrgyzstan sold shares in a Uzbek cotton and textile firm, held through a British limited liability company, for US$14 million. The purchaser, a Luxembourg company, paid a US$1 million deposit.

The court decision says that the deal fell through after the Kyrgyz citizen failed to evidence that his Uzbek company successfully acquired a government cotton-yarn factory for “zero cost” by the contractually stipulated date. An order was made for the return of the deposit plus interest and costs.

A Swiss Criminal Order from July 2019 indicates Mirakbar Yakubzhanov was found guilty of defamation and libel. He was ordered to pay a fine and was given a suspended sentence of three years. Registered mail sent to Mirakbar Yakubzhanov’s UK address seeking comment did not receive a response.

A privatisation revolution?

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan’s authoritarian regime steered a cautious economic path. State enterprises still dominate significant swathes of the national economy, while a class of business leaders have emerged primed by political patronage.

Uzbekistan’s state-run cotton sector has been a key source of export earnings. But these earnings have come at a significant cost. State cotton quotas fulfilled by regional governments have promoted a dependence on coercive labour recruitment practices. Children, public servants and even doctors have been marched into the cotton fields to meet state targets.

The cotton privatisation programme aims to change all that. The Economist claims this is a win for Uzbekistan’s long suffering workers, who will benefit from improved conditions and pay. The International Labour Organization has also lent its support to the cluster system, with one caveat: its potential hinges on attracting responsible investors.

For many commentators, the rapid privatisation of Uzbekistan’s cotton industry offers a transformative road out of a past tainted by forced labour and corruption. There remains a real risk, however, that this will be a circular movement given the apparent lack of due diligence and corporate accountability.

All images courtesy of Ulster University and Uzbek Forum for Human Rights.